Chapter 19.5 — Northern Midlands. Albweiss Mountains. AM Guild - Yu - Inner conflicts

-

-

-

-

-

-

But what was it? What had she done to him? What exactly had she told him? What had she asked? The memory ran from him like desert rain over salt flats; brief and fickle and storm-torn, shivers of thought that sank into nothing. He caught only fragments, droplets that evaporated the moment he reached for them. They left only a crust of meaning — Oracle. Time. Wait.

Why him? Were oracles not some special, super rare, high-level magic stuff? Did she truly think he could do such a thing? Why would she? She had said they would speak again. What would happen when that moment came?

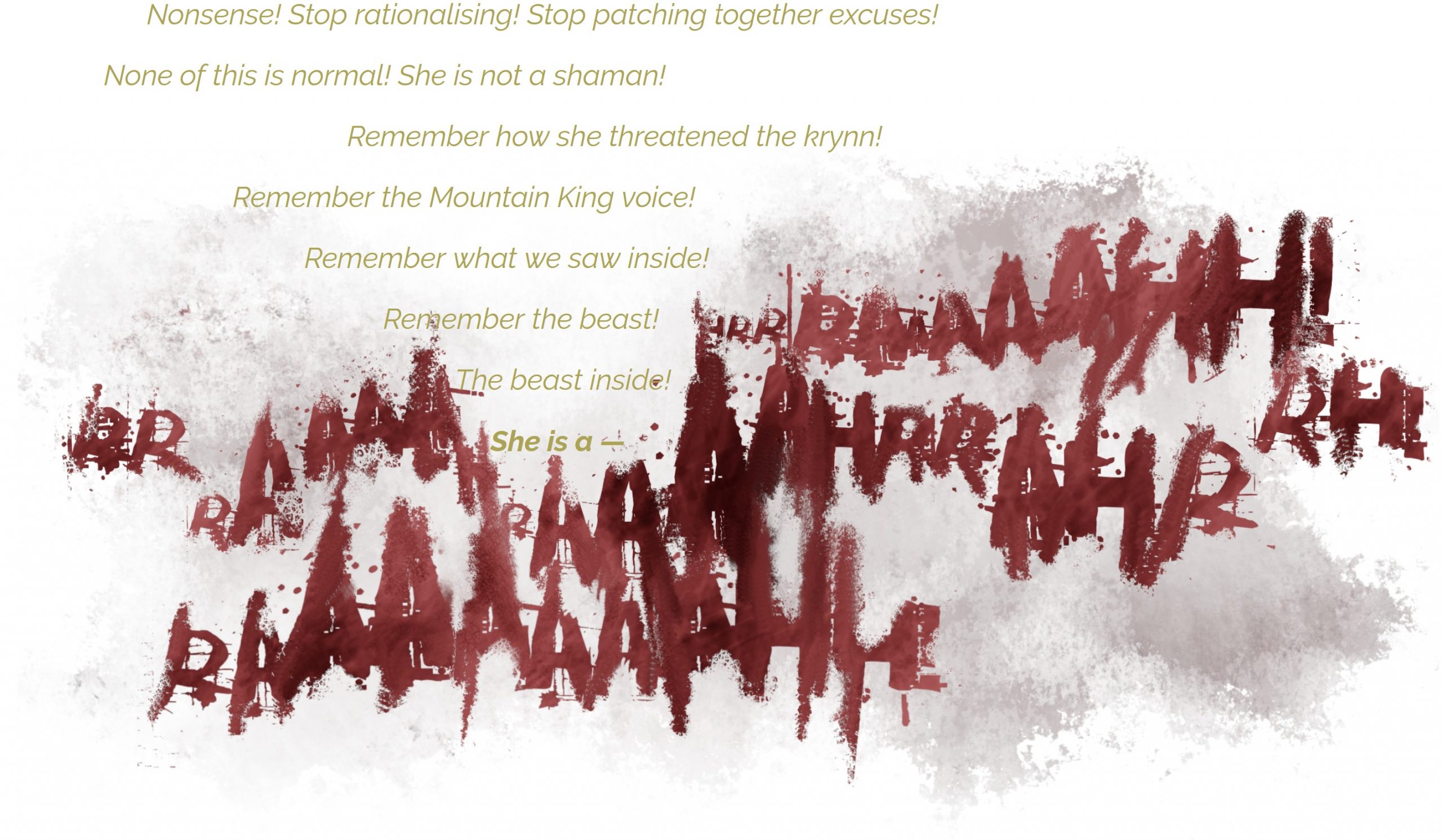

And did the others know? Did the guards understand who she was? Or was it only Yu — because he had heard her? Bubs, Deltington, and the guests in the common room; none of them had reacted when her voice struck. They had shown no dread, no awe, not even a glance that betrayed recognition. No one had reacted in any way, while the sheer magnitude of her PRIDE and POWER and PURPOSE had driven Yu into collapse. The unbearable force of her presence had unmade him. The memory made him sick, more sick than he already was. It made him shake all over. Yu remained bent over the table and left his face buried in his wings. Like that, it took several rattling void breaths for the worst of it to pass; wet, broken, muffled gasps pressed through the mask. At last, the spasms waned and he steadied himself. He stilled his legs, reasonably, and released enough tension to rest his upper body on the table, at least partially, gradually. Yet he could not shake the conviction that even someone who knew the <img alt="image" height="29" src="https://glasswizardchronicles.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/018.8-The-Glass-WIzard-Webstory_Psychological-Fantasy-Magic-Webseries_The-Duckman_Chapter-Part-2_Queen_small.jpg" width="58"/> could not have endured the revelation of her being. No one could ignore such a condensed eruption of presence. It had been so much stronger than the deflection pulse. At least the krynn should have reacted, with how intuitive and impulsive he was. The borman, bound to his human, should have broken through the door the instant he feared her harmed. But no one had moved. No one had felt. No one had seen. No one had heard.

It had been only Yu.

That, in itself, was nothing new. He had always heard what others could not. It had been that way all along the Snowtrail — murmurs that rose from the cracks within the stone, whispers that trailed the wind, songs that shaped the cold into meaning and then withdrew before he could understand; distorted and disturbing sounds that were never truly there in the same way that they existed everywhere, all the time.

Yu opened his beak and let out a long, dragging breath. A lot of spit came with it. It slicked his feathers, but he just let it flow.

Was that … all this was? Just … more of that same fevered hearing? Had he been so overwhelmed by the <img alt="image" height="30" src="https://glasswizardchronicles.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/018.8-The-Glass-WIzard-Webstory_Psychological-Fantasy-Magic-Webseries_The-Duckman_Chapter-Part-2_Queen_small.jpg" width="60"/> not because of what she was, but because of what he was?

What exactly had he heard?

Who, truly, was she?

----The <img alt="image" height="30" src="https://glasswizardchronicles.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/018.8-The-Glass-WIzard-Webstory_Psychological-Fantasy-Magic-Webseries_The-Duckman_Chapter-Part-2_Queen_small.jpg" width="60"/>.

A queen.

The word was right there, but at the same time, the meaning was not.

Yes, there were queens in this world. The Southlands festered under various crowns. Kingdoms rose and rotted, and among them survived a handful of monarchs who still defied the King Brothers' reach.

Could any such queen become a shaman? Almost anyone could, could they not? Not just commoners desperate to escape their broken lives, but royalty also. Not just weak people, but … powerful people also.

The Midlands held many powerful races, bloodlines and individuals. There were master wizards at the academies, witch-mothers who ruled the mountaintops and marshes, the ker who ate from storms, and many beastkin who roamed the southern forests and fens. Anywhere from the western swamps to the eastern sea, you could meet deadly ethereal beings with unfathomable abilities, such as sprites. Even lesser creatures like orks possessed crude workings of magic. The deflection pulse alone proved that there were individuals who could crush others with nothing more than the weight of their presence, without ever touching them.

Powerful people. People with devastating presences. All of these people could become shamans.

But what happened when they did? What happened when a person that was already extraordinary, gifted with superior senses or trained in the highest forms of magic, underwent the transformation?

Until today, Yu had thought shamans did nothing but healing. That they submitted their old selves for the knowledge to mend and to soothe. That had been what he believed, though mainly because there was a shaman with the Mausoleum wizard, helping with treatments, as far as rumours reached. But the <img alt="image" height="30" src="https://glasswizardchronicles.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/018.8-The-Glass-WIzard-Webstory_Psychological-Fantasy-Magic-Webseries_The-Duckman_Chapter-Part-2_Queen_small.jpg" width="60"/>, speaking through the guild shaman's voice, had told him otherwise. Every transformation was different. The outcome depended not on the ritual, but on the person.

So then, did people just keep their original abilities? Did they develop? Did they grow sharper, stronger? If shamanhood did not demand an exchange of skills, a sacrifice of one self for another, if it did not strip but preserve, if it did not consume but cultivate, then why did not everyone seek it? Why would anyone remain as they were, if the transformation could change their body just how they wanted it to be, even regrowing — even restoring what had been lost, or granting what had never been given at birth? What was the downside of it, if it gave power without taking?

If this is how it worked, then … had the <img alt="image" height="30" src="https://glasswizardchronicles.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/018.8-The-Glass-WIzard-Webstory_Psychological-Fantasy-Magic-Webseries_The-Duckman_Chapter-Part-2_Queen_small.jpg" width="60"/> just been …

... a very powerful person, before?----------------

---Had Yu simply … overreacted? Was the terror and awe he had felt just a natural reaction to someone of her standing and power, to someone of royal magnitude who had, perhaps over decades, cultivated exceptional abilities and then kept them when entering shamanhood?

---Was all of this his own fault — the fault of his hearing, that cursed excess of perception which drew in what others could not bear? Was this only his sickness, his weakness, his overreaching sensitivity to things that should remain unheard? Maybe he had felt her too deeply because he had never stood before absolute and unrestrained power before? He came from nowhere. From a backwater place of mud and hovels where strength meant the fists of bormen and the hides of beasts; where no wizard lingered long enough to teach, and witches struck down anyone who rose too high above the dirt.

----------Was that ---why?

-----Was a powerful queen who became a powerful shaman just …

----------------------... normal in the greater world?

-------------Was this what power looked like everywhere else,

----------------and Yu, in his ignorance,

----------had mistaken the discovery of her presence for a grand revelation,

--------------------and her superiority for divinity?

-------A brutal, bestial scream tore through Yu's insides; a horrendous roar no living beak could ever form. The wanting part roared to drown out the voice of terror.

Yu clenched his eyes shut and drove his forehead into the table, once, twice, thrice, again, and again, and again, until the motion lost all meaning, and still, the pain was still too dull and too distant. He snapped his beak together, fast and hard. It was not laughter. It was to uncoil the crushing tension in his jaw that prevented him from screaming or even speaking. It was the desperate mimicry of sound, any sound, anything at all that was not the voices within.

Still clapping his beak, he forced the air from his lungs until he reached the edge of suffocation where breath became strain and his groan broke into a ragged tremor and then further, until it thinned into a shivering, voiceless hiss, and further still, until it became a distorted void breath. The pressure in his skull shifted. His head swam. At last, reason, frail and blinking, found its way back into the wreckage.

Yu did not know what she was. He did not know if it was possible to fake to be a shaman, or how to tell the true from the false. He knew nothing of significance, never heard anything of consequence, and all he believed was superstition spun into story. Shamans came and went. They wandered between places, passing like weather through the lives of villages, sometimes lingering for a few days, other times months. They watched or traded service for shelter, whatever that meant, if not healing. None had ever stayed with the people of the settlements. Their paths ran further south, along the Albweiss regions and beyond. The only shaman to ever reside in the Barnstreams was the one at the Mausoleum, and she had come less than a year ago. Before her, only one other had crossed Undertellems in the last decade. That is, not counting Jerikall —

The name crashed into him like thunder. His whole body jolted upright. His wings tore from his face and struck down onto the workbench with a sharp slap. Then came the storm, a lightning storm of thought, binding and blinding. Yu tensed. His wings pressed against the table. His talons clawed at the stone, scraping and flexing, left, right, left, right, as it ran over him. Each realisation flashed sharper than the last.

Could Jerikall tell him more? Was he the one person who could make sense of all this? He seemed newly changed, yes, but still, he must know how it worked. He must have been instructed. Was this knowledge sacred? Was it forbidden, or could it be shared? If Jerikall knew anything of the <img alt="image" height="30" src="https://glasswizardchronicles.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/018.8-The-Glass-WIzard-Webstory_Psychological-Fantasy-Magic-Webseries_The-Duckman_Chapter-Part-2_Queen_small.jpg" width="60"/>'s transformation, would he tell Yu? Would it be safe to ask? Surely a shaman would not serve a syndicate — no, never, not a true one. Surely Jerikall would not conspire with one wizard to deceive another, nor lend his craft to the Shaira, nor to a scheming Witch Blessed. For that would mean taking sides, and no shaman took sides. If Jerikall was real, he was safe —

--------Why, then, is he with them?

The question caught and tore it all out in an instant — the storm of thought, the trembling light behind his eyes. It came like a hook through the chest. It seized the heart of hope, every last filament, and dragged it out, dragged it still. Without the hope to bind them, the thoughts collapsed. The noise fell away. The lightning went dark. What remained in that darkness was the single voice of burning terror, the one that swam too deep to grasp.

---He is with them. His loyalty is with them, not us. Whatever we reveal to him, he will pass on to them. They will kill us. Think about it. He cannot have joined them, he cannot have travelled with them for weeks without knowing what they do. This means he is hiding something. This means he is like them. What if he is like the Queen? How can you be sure she is not also a mon— NONE! None of them is like her! No one! No one is safe. She is all we need. All we are is for her. There are no safe people here. She has all the answers. She is the answer to everything —

Yu's legs gave in. He collapsed into a crouch, low and cramping, with his legs bent, his back bent forward and his head buried between his knees. He wrapped his wings tight around his body, and pressing the feathered stumps into his face, pressing harder still against his beaks until the air thinned, and then he screamed into them while trying, in the same motion, to suffocate the sound.

This. Was not. Him!

----This. Could not. Be. Him!

-

He had to believe the wanting part would not stay. He had to believe it could be taken out of him, torn out, driven out, scraped away. He needed to know that it was not his, that it was not a part of him in the first place, not something of him, but something in him, something foreign, invasive, destructive — a splinter, a parasite, a poison.

--

Like -------------------------

a poison--------------------------------------------------

Unauthorized use of content: if you find this story on Amazon, report the violation.

------------------------------------------------needle

--

-----------------He could not let it sink in deeper,

----------he had to keep pushing and pulling at it.

Yu pushed himself off the floor.

We need to keep going.

Keep going, as if it did not exist. Keep moving, as if it did not sting and bite and burn beneath every breath. As if nothing had happened in that half hour that had not even been half an hour. Yu needed to believe this, so that he could wear the mask. So that he could become the mask, the still-whole self he had been before.

Until then, remember who you were. Remember who you must be. Pretend.

Fasten the mask. So tight that there would be no room left for the wanting part — and none for the other, the hysterical, trembling, terrified self. Tighten it until the mask became the face again.

Now, work.

Before he could set his mind to it, Yu found himself circling the workbench again, the same path, the same practice as before. With each step, he looked beneath. At each corner, he opened and closed the cupboards that doubled as the table's legs. There was nothing in there. Only bowls, plates, and silence. Like that, he completed the circle and came back to the hearth. Still too restless, he turned again, but in reverse, clockwise. This time, he searched for something to remember himself by. He also searched for something to drink. His stomach was still sick with stew.

Left of the entry, on one of the upper shelves, he found several bottles of four repeating kinds. Their glass caught the orblight in dull shades of brown and black. Yu recognised two of the labels. Among them was Grainthistle Black.

-It made him pause,

---because it made him remember.

They called it The Trader's Pride. It was a real thing, the pride. Those who brewed it boasted their bottles like trophies, front and centre for all to see. It meant they had seen it all, because real Grainthistle demanded ingredients from every corner of the Barnstreams, from the dead and deserted Northlands to the streaming south, and as far as the first white reaches of the Albweiss where the selder settled in the west. It took endurance and calculation, coin and connections to conquer distance and decay. You needed to gather everything in time and in the right order of harvest, so that the first ingredients did not rot while you were still hunting the last. There were no shortcuts and no substitutes. So if you made Grainthistle, it meant you really made it, as a trader. It was reputation in a bottle. Not just the traders acknowledged this, but all the regular people knew. To the common customer, a front-row Grainthistle promised an experienced, well-stablished merchant who had mapped the settlements through his own exhaustion and returned with a wide variety of news and novel wares from all over. It meant he had crossed the wastes and survived them; that he had negotiated his way through ruin and returned with the taste of distance preserved in glass. And he would offer you a glass, first thing. Before you bartered and bought anything, you tasted the drink.

Of course, no one stopped you from simply buying all the ingredients from someone else, without ever setting one talon outside of your own village, but the first thing that someone would do – after cashing in on your counterfeit pride – was to see to it that all the other traders knew. And oh, those guys would let you have it. Yu had seen a tairan who had gotten it, three or four years back. They had made him pay, as the traders said. Needless to say, he left the settlements shortly after. Well, shortly after selling all his property to pay the Mausoleum wizard to mend what had been broken.

Yu knew all this from his first official lesson in economics, back when Tria had hired him a private tutor. Though, she had never meant for Yu to become one of those petty market merchants who scraped a living by running around everywhere and bartering their thisses for thats. She had wanted an administrator, someone who directed things on a grander scale, a numbers guy who could shape trade between entire settlements rather than haggle over rope and fish. Still, to handle the big things between settlement authorities, you had to understand how it all worked on the smaller scales. You had to know what people wanted and how they weighed worth against this want. You had to see how they handled petty trades and cheated private bargains.

Tria did the big things, and she walked and talked like she owned the scales. Bornicay, before she would waste her own time on Yu, had been there to show him the small stuff.

With the Grainthistle, Bornicay had attempted to introduce Yu to the art of trading in what he must have hoped to be an enthusiastic, engaging, hands-on experience. He had said something like, Go on, take a sip! This is your first taste of this promising profession. The taste of the trade! Once you have travelled the whole Barnstreams, you will make your own Grainthistle. And then, so I hope, you will look back on this moment now, proudly, and see just how far you have come. He had said it like it were a promise, all open palms and easy laughter. Needless to say, Yu had never been a hands-on guy. He had hated all of it, the idea, the lesson, Bornicay with his fake friendliness, and the drink. The taste was bitter and resinous, and it had left his beak dry for hours.

He would not try it again today. The bottles on the shelf looked darker than he remembered. The pride inside seemed thickened, sunken, like the idea itself had curdled. He felt no urge to drink from it. He felt sick already, and he would not wager on the off chance that his tastes had suddenly, inexplicably changed.

The second drink he knew was Sharran Vey, a desert spirit drawn from sastan pulp. Yu recognised the bottle before he read the label. It always came in an odd square block of dark glass that looked more like a small casket than, well, a bottle. The thing had a broad mouth, made to contain the preserved areole of the sastan cactus within. Distillers packed the pulp whole, so the spirit matured around it without decay, but if the areole rotted in direct sunlight, burst or were crushed, the liquor turned lethal. With that, the colour and shape of the bottle was half safety, half spectacle. It spoke of skill as much as risk. Every indulgence was a wager with death.

And the risk was real. People died from this, every year. They deserved it. Well, not the poor who had nothing else, but the ones who took to it deliberately. Some people sought that very risk, drinking Sharran Vey daily for just that reason. They were the ones who believed backwater was for bathing, the sort of people who claimed that the desert ran in their blood and such. They needed to dignify their shit life and glorify their suffering, just to taste some purpose, however disgusting and deadly. Yu was not one of them, and neither was Tria, though she pretended otherwise when it suited her public image. To Yu, Vey had always been a last resort, the drink of desperate desert wanderers who had run out of water and faith alike. It was vile, kin to the Grainthistle but more bitter. And yet, it was familiar. There had been a drought seven years past, so severe that everyone had been forced to drink it for weeks.

Yu wanted to drink it now, if only to summon that memory of home, that scorched familiarity. But he hesitated. The areoles inside looked right, pale and dense like preserved flesh, with no broken bits floating around, but the label was wrong. The letters warped into something that read more like Sharny than Sharran Vey. It unsettled him enough to step back from the shelf. Again, he would not risk it.

Other bottles bore names he had never heard or could not read, some still sealed, others half-drained. Yu knew none of them and did not dare try. Not only because pulling them down and prying the corks would be a pain prone for another disaster. Not even because Bubs might object. But because fina could not stomach most of what the tairan and the traders brewed, and Yu did not assume the rest of the world to be any more considerate. Everything that Tria had ever received from outlanders had been strange spirits and corrupted concoctions, like their many dishes of dough that soured the gut and sickened the blood. There ought to be a law against that sort of food. It was as though they made it unfit on purpose, to keep it to themselves.

Disappointed and disillusioned, Yu gave up on the cupboards and shelves. The sink opposite the hearth offered something more immediate. It was cut from the same stone as the wall, with a crude pipe system much like the one in the bathroom, which meant one singular spout above, and one broad drain below, at the centre of the sink. Like with the barrel and the toilet, a thin slate blocked the downward outflow. Yu pulled it halfway, and a stream gushed forth, striking the basin and spreading over the darkened trough before coiling into the drain.

He watched it. Yu just stood and watched the water. His eyes followed the flow as it bled across the shallow curve, sometimes fixing on the slit where it gushed in, sometimes on the grated hole where it vanished. After a while, he noticed that the stone beneath the stream was darker than the rest. It was grey shading to black, while the sides of the sink kept the same pallor as the walls. The stone was neither damp nor did it seem stained on the surface, but the colour had permanently changed. Yu wondered why. The water was clear, the rock was pale, and yet, where they touched, something had deepened over time. How did that work? How could one transparent thing make another bright thing darken? Where did the dark come from?

While surely interesting for all of ten seconds, this was not an observation to distract and fixate on for long, so eventually, Yu bent down and drank straight from the flow.

It did nothing. It did not change any feelings of hunger or thirst. His stomach only swelled with the same dull pressure.

-

Well, if feeding himself made no difference, then perhaps feeding the others would. He had no choice. He had to do it.

Yu returned to the hearth and took his emptied bowl from the stool. He set it on the workbench and replaced it with a clean one. Two might have fit, but he feared knocking them over the edge. One at a time was fine.

He climbed the second stool. The steam pressed heat into his feathers. The pot breathed into his face; fat and smoke and sour sweetness. Yu bent forward, gripped the ladle with trembling talons, and dipped. He spilled half before it reached the bowl, cursed under his breath, and scooped again, and again, and then a fourth time, because he had fed so much to the floor each time that three were not enough. Then he set the ladle aside, climbed down, stepped straight into the spills on the floor, of course, tried to scrape it off, failed and gave up, pressed his wings around the bowl and carried it to the tray.

Then he went back again, placed the second bowl on the stool turned table, and got up the suicidal stool once more. He grabbed the ladle, again, filled the bowl with three shaky half-scoops and the floor with more spills, again, put the ladle back down, again, got down himself, again, and brought the bowl back to the workbench, again exchanging it for an empty one.

That was the ritual. He did the same with a third and fourth bowl. Climb, grab, dip spill pour, dib spill pour, dip spill pour. Look at the mess. Climb down, step into shit and curse. Grab the bowl, lift, carry, place, exchange, return. The rhythm swallowed him whole. There was no sense of progress, only the circling persistence of motion performed to fend off thought. It went on and on, slow and stupid, like everything else that should have taken ten seconds if you were a normal person and not a cripple parodying a cook. But then, at last, at long last, the tray stood ready, with four bowls filled.

When he tried to lift the tray, it resisted him. He wedged it to his chest with his wings clamped on either side, but no matter how hard he squeezed, he could not hold the weight without losing his grip. But it was not the weight that unnerved him. He waited for the exhaustion and the pain. As Yu fumbled with the tray, again and again rearranging his stance and hold, he waited for it; for the throbbing of his burns where the skin was raw, for the sting in his sides and the tug in his back, for he tremor in his legs. None came. His body still felt very far away from the surface. No part of him wanted to recover and relive the exhaustion of the day and the pain from bis wounds, but just like with his lack of hunger, it worried him. Because he should feel it. It should be there. It had been, during the whole day. It was not gone. It had only sunk deeper, drawn down into that other pulse, the one that wanted, and would not still.

------The other pain.

---The other aching.

---------The other HUNGER.

Get a hold of yourself!

Yu tried to. He really did. But he could not even get a hold of the fucking tray. His frustration rose in waves. His wings shifted, adjusted, slipped again. No grip seemed right. There was never enough room to secure his hold. The tray was too broad and flat; the rim too narrow to catch. He tried locking it between his upper wing and the blunt stump of his lower one, bent awkwardly round his elbows, but he could not properly lock it in. It was basically a flat board on a flat table that he tried to pick up with his elbow tips.

Eventually, Yu eased one side of the tray over the edge of the table. That felt like progress — for all of three seconds. One end raised meant nothing if the other still clung to the wood. So he pushed further, shoving the tray toward the corner of the table, until both short sides hung out into the air. It was, in principle, a plan, just not a viable one. He could not free much of the rim, less than a third on each side, else the whole thing would tip.

From there, he tried again. He pressed the long side into his chest and arched backward until it found a shallow rest along his breastbone. It was the best he could do. It was not good enough. He knew it would fail. But because he was out of ideas, he did not want to believe it. So he lingered there, half-clutched, half-bound to the tray, weighing the thing against the risk of motion. Could he rush it? Could he make it if he just ran — burst through the doors, right up to the first table in the common room? It seemed impossible. It seemed like a very, very bad idea. Then again, there was no sense in delaying any longer. Yu could either drag out the tray now, or drag out the inevitable.

Patience abandoned him first. He lifted. The weight bit into his ribs. The bowls shuddered. Stew lapped at their rims. One backward step, one tremor in his grip, and the whole thing began to slide. Panic seized him faster than thought. He bent forward and slammed the tray back down onto the workbench. It struck hard but landed upright. A tide of stew sloshed over the edges, yet the bowls stayed standing.

After that, Yu simply stood there, bent over the tray with his wings resting on the table, breathing hard and staring down at the bowls, at the mess pooling round them, and at the waste slicking the table's edge. This was four servings of stupid decisions.

At last, he gave in. He would take them out one at a time. So he removed the first bowl, then the second, and then the third, each set down a few steps to the right, beyond the spills. When only one remained, Yu returned to wrestling with the tray, spinning and shifting it about, pushing it towards the edge while readjusting the lone bowl again and again. It was an utterly pointless struggle underlined with many curses. A pathetic waste of time. It was so stupid you would not even believe it was a parody.

Then suddenly, long before he would ever grasp the thing, he grasped a much simpler, much lighter truth;

-

that a single bowl balanced on a flat tray

was harder to carry than the bowl alone.

There was absolutely no fucking reason

to use this fucking piece of shit tray

if he had just one fucking bowl on it.

He could carry. Just. The bowl.

Just. The. Bowl.

The sudden realisation made Yu question, in all earnestness, whether he was mentally retarded but just did not know.

-

The human's cry from beyond the door snapped him out of it. Yu seized the bowl before him – no tray, no second guessing – and carried it to the kitchen door. Pressing his back to the wood, he dragged the handle down with his elbow.

Just as he turned toward the common room, his gaze flicked upward to the mural above the door; that grotesque sprawl of arachnids locked in battle with the desperate humanoid figures, masses of limbs and abdomen knotted into a monstrous coil. The sight made him pause. For a moment, he simply looked, craning his neck to see from directly beneath. He waited for the shapes to stir, for the bulging bodies to strain against the plane of the wall, for the jointed legs to twitch toward the orblight. In a twisted way, he wanted them to move — for something outside to echo the crawling within.

But the painting stayed still. The fear was dead. Nothing in pigment could reach him anymore. In the end, it was nothing but an ugly, ridiculous, unreal thing.

Yu passed beneath it.

-

-

-

-

-

--

NOVEL NEXT

NOVEL NEXT